What are phytocannabinoids?

Contents:

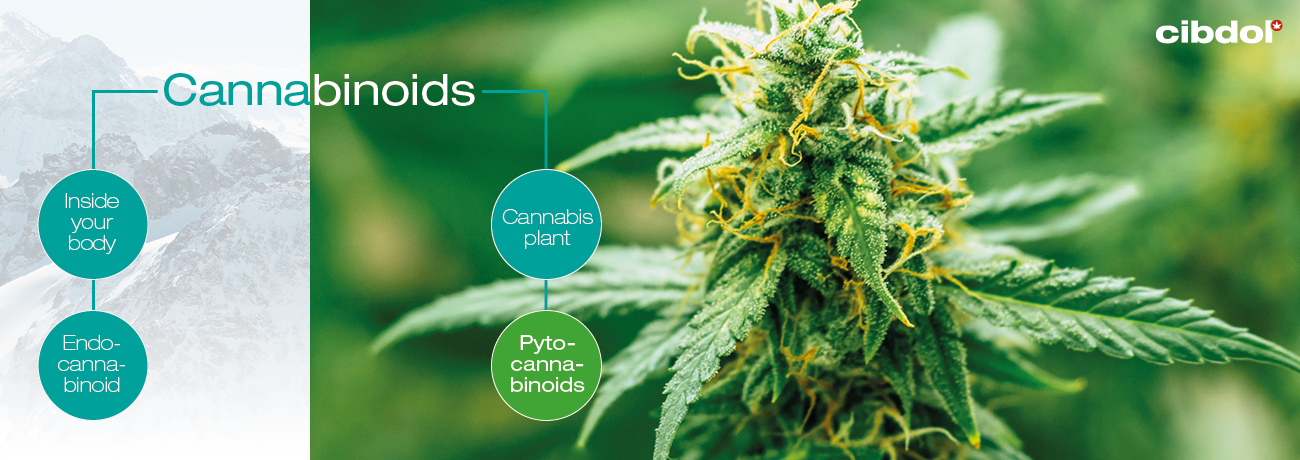

The cannabis plant produces hundreds of chemical constituents—from cannabinoids and terpenes to flavonoids and lipids. Among these, the phytocannabinoids [phyto = Greek (φυτό) for "plant"] are the most unique. They’re not all exclusive to the cannabis plant, but the species contains some of the highest concentrations of these compounds.

Because these molecules are produced in plants—and not in the human body or a lab—they are referred to as phytocannabinoids, hereinafter referred to as simply cannabinoids. Humans have used cannabinoids for thousands of years for various purposes—spiritual, therapeutic, and recreational.

Such long and consistent use reflects just how valuable these molecules really are. Modern science has probed and prodded many cannabinoids in search of potential therapeutic and industrial uses. After only a few decades of study, researchers have identified over 100 cannabinoids in the cannabis plant alone.

Introducing cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system

Cell, animal, and human studies have discovered, in part, how these chemicals work in the body. Identification of the endocannabinoid system reveals how cannabinoids can mimic regulatory molecules (endocannabinoids) produced within our own bodies. These findings paved the way for understanding how these molecules produce their effects.

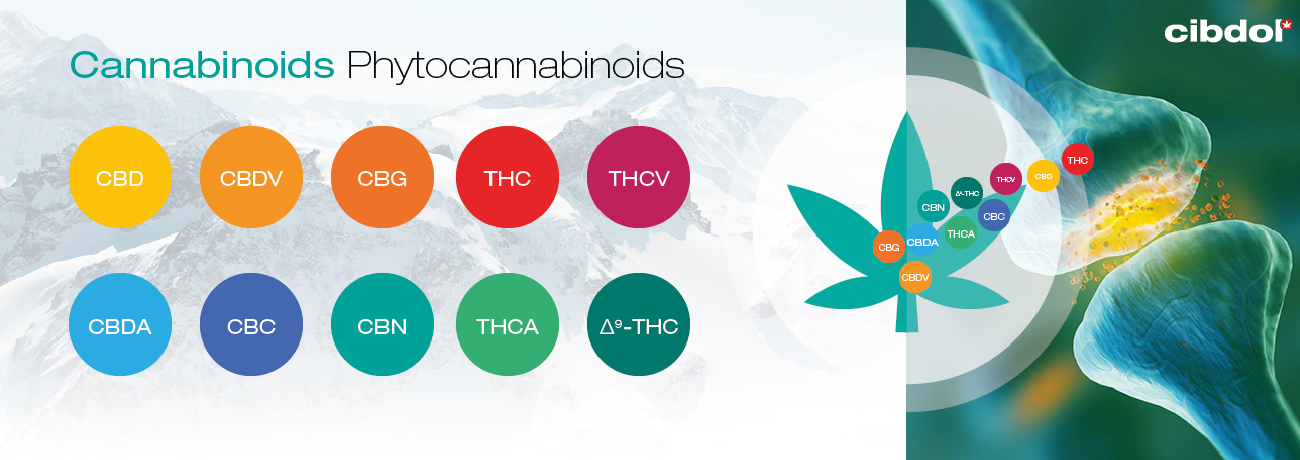

Perhaps the most widely known cannabinoid, THC, produces the psychoactive high associated with marijuana. However, researchers have also found the unique cannabinoid to hold promise in soothing physical aches[1], upset stomach, and low appetite[2].

Cannabis also offers many non-psychoactive cannabinoids. For example, research has found CBD to produce a wide array of positive effects on the body. Because of this, CBD has become an extremely popular supplement used to support homeostasis (internal equilibrium).

THC and CBD are the predominant cannabinoids in most modern cultivars. However, other, less abundant cannabinoids have also demonstrated promising effects in research settings. CBG, CBN, CBC, THCV, CBDV, and others have exhibited a broad range of effects[3].

Cannabinoids also appear elsewhere in the plant kingdom. The so-called “dietary cannabinoid” caryophyllene—a terpene also synthesised in cannabis—can be found in black pepper, hops, lemon balm, cloves, and rosemary. Caryophyllene is considered a cannabinoid because it interacts with the CB2 receptor of the endocannabinoid system. Cannabinoids that influence the other major cannabinoid receptor, CB1[4], occur in Salvia divinorum, carrot, kava, New Zealand liverwort, and maca.

How are cannabinoids produced?

Plants produce cannabinoids as secondary metabolites[5]. They are not directly involved in growth, development, or reproduction. Instead, they help plants survive by defending against pest species and extreme temperatures.

Cannabis plants produce cannabinoids in tiny mushroom-shaped glands called trichomes. These translucent structures produce other metabolites too, such as aromatic terpenes. The series of chemical reactions that create cannabinoids is referred to as cannabinoid biosynthesis[5].

The process begins when coenzyme A and fatty acids converge. This gives rise to a series of chemical reactions that eventually form CBGA and CBGVA—two major cannabinoid precursors. Enzymatic reactions convert these molecules into different cannabinoids. For example, the enzyme THCV synthase transforms CBGVA and CBGA into THCV. In contrast, the enzyme CBDA synthase converts these molecules into CBDA.

All of this magic occurs primarily in visually stunning and aromatically pleasing cannabis flowers. Eventually, trichomes churn out cannabinoids and other metabolites in the form of a viscous resin. Manufacturers then use this resin to produce a whole range of products, from oils and other extracts to crystals and cosmetics.

Summary of cannabinoids

Cannabinoids are secondary metabolites found in the cannabis plant and a few other species. They work to keep cannabis plants healthy, and science has also revealed their therapeutic potential in humans. So far, we have only studied a handful of these interesting molecules in-depth. Further research will continue to elucidate the full value of cannabis and other cannabinoid-producing plants.

[1] Weber, J., Schley, M., Casutt, M., Gerber, H., Schuepfer, G., Rukwied, R., Schleinzer, W., Ueberall, M., & Konrad, C. (2009). Tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta 9-THC) Treatment in Chronic Central Neuropathic Pain and Fibromyalgia Patients: Results of a Multicenter Survey. Anesthesiology Research and Practice, 2009, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/827290 [Source]

[2] Ekert, H., Waters, K. D., Jurk, I. H., Mobilia, J., & Loughnan, P. (1979). AMELIORATION OF CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY‐INDUCED NAUSEA AND VOMITING BY DELTA‐9‐TETRAHYDRO‐CANNABINOL. Medical Journal of Australia, 2(12), 657–659. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1979.tb127271.x [Source]

[3] Russo, E. B., & Marcu, J. (2017). Cannabis Pharmacology: The Usual Suspects and a Few Promising Leads. Cannabinoid Pharmacology, 67–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.004 [Source]

[4] Russo, E. B. (2016). Beyond Cannabis: Plants and the Endocannabinoid System. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 37(7), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2016.04.005 [Source]

[5] Flores-Sanchez, I. J., & Verpoorte, R. (2008). Secondary metabolism in cannabis. Phytochemistry Reviews, 7(3), 615–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-008-9094-4 [Source]

[1] Weber, J., Schley, M., Casutt, M., Gerber, H., Schuepfer, G., Rukwied, R., Schleinzer, W., Ueberall, M., & Konrad, C. (2009). Tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta 9-THC) Treatment in Chronic Central Neuropathic Pain and Fibromyalgia Patients: Results of a Multicenter Survey. Anesthesiology Research and Practice, 2009, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/827290 [Source]

[2] Ekert, H., Waters, K. D., Jurk, I. H., Mobilia, J., & Loughnan, P. (1979). AMELIORATION OF CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY‐INDUCED NAUSEA AND VOMITING BY DELTA‐9‐TETRAHYDRO‐CANNABINOL. Medical Journal of Australia, 2(12), 657–659. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1979.tb127271.x [Source]

[3] Russo, E. B., & Marcu, J. (2017). Cannabis Pharmacology: The Usual Suspects and a Few Promising Leads. Cannabinoid Pharmacology, 67–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.004 [Source]

[4] Russo, E. B. (2016). Beyond Cannabis: Plants and the Endocannabinoid System. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 37(7), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2016.04.005 [Source]

[5] Flores-Sanchez, I. J., & Verpoorte, R. (2008). Secondary metabolism in cannabis. Phytochemistry Reviews, 7(3), 615–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-008-9094-4 [Source]